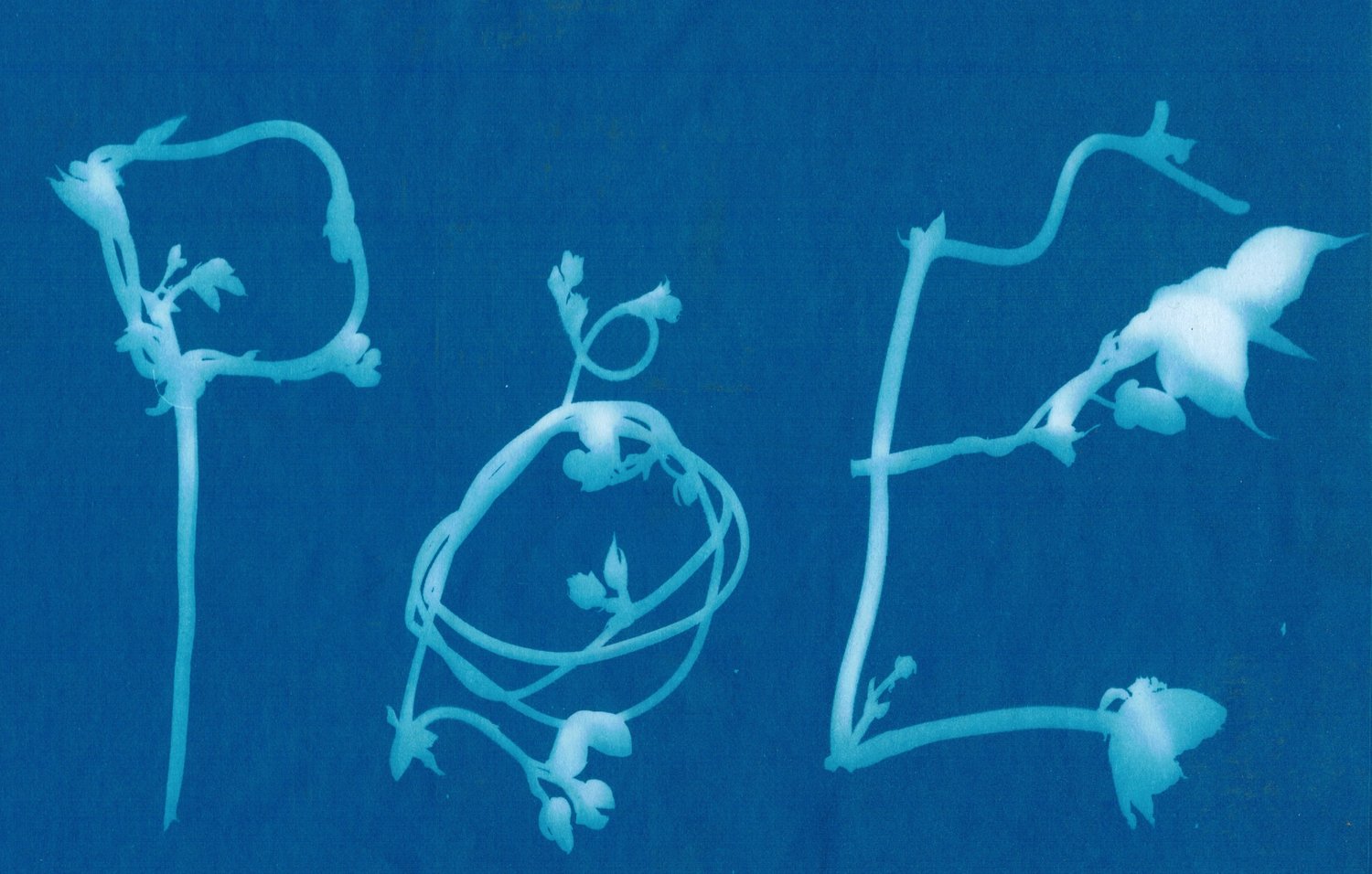

As participants in the PPEH Intersecting Energy Cultures Working Group, POE created a comic, Evacuation Plan, and a corresponding policy brief on energy, environment, and decarceration for New York State.

Four urgent steps toward environmental justice in New York State: 1) year-round healthy temperatures for incarcerated people, 2) transparent disaster and evacuation planning for prisons 3) frequent and transparent environmental monitoring in prisons, and 4) the decarceration of vulnerable incarcerated people through sentencing and parole reform.

Environmental Justice and Decarceration in New York State:

Abolitionist Steps (PDF)

Introduction

Prisons are well-documented sites of extreme and often unmitigated environmental injustice–where marginalized populations experience additional vulnerability related to pollution and climate change. These violations of the health and safety of incarcerated people have become increasingly visible, especially with the recent introduction of federal legislation, the Environmental Health and Prisons Act and the Declaration of Environmental Rights for Incarcerated People. As the effects of climate change impact incarcerated people in distinct and disproportionate ways—dangerous temperatures, lack of transparent evacuation planning, disease, and even increased violence—sentences in state carceral systems are getting longer, dramatically increasing the range of health and safety risks people behind bars face. New York, a progressive state that has significantly reduced its prison population since its height in 2000, has the opportunity to take concrete steps to address the concerns through measures like temperature control, environmental monitoring, and transparent disaster preparedness, all of which are recommended safety measures along the path toward the most effective form of environmental justice for people in prison: decarceration.

Background

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency suggests that environmental justice is achieved when “everyone enjoys the same degree of protection from environmental and health hazards, and equal access to the decision-making process to have a healthy environment in which to live, learn, and work.” However, carceral facilities, the Prison Policy Initiative reports, are “a daily environmental injustice.” Through our research and collaboration, Products of Our Environment has identified several interrelated policy goals—or “abolitionist steps”—aimed at improving the lives and health of people imprisoned in New York State while moving toward the goal of abolition.

Policy Recommendations

By centering environmental justice claims and priorities in policy decisions about where prisons are located, how those carceral spaces are monitored, what information is available about them, and how many people are in them, New York can build strong connections between social and environmental justice to strengthen policy and coalition-building for both. We recommend:

1) Year-round healthy, livable temperatures for carceral facilities

2) Transparent and concrete evacuation and emergency planning

3) Environmental health monitoring and climate change mitigation efforts

4) Decarceration through parole reform

Healthy Temperatures

Most state prisons do not have temperature control throughout the facility, which has serious health and mortality impacts for people held within them. A recent study found that the Northeast, including New York State, sees the highest mortality in prisons associated with extreme heat relative to other states.

Senate Bill S7781A, which lays out provisions for mitigating the effects of extreme heat in state prisons, establishes a starting point for protecting incarcerated people from extreme heat. However, the bill does not call for air conditioning or temperature thresholds and contains unclear language such as “to the extent possible” when describing mitigation plans. The bill, then, must go further in establishing a heat threshold in accordance with current medical recommendations.

Environmental Monitoring

Building from The Environmental Health in Prisons Act, New York should collect environmental and health data from state prisons, make data accessible to incarcerated people, and take concrete steps to improve the environmental and health conditions, emphasizing decarceration rather than sustaining current populations.

Crucially, the Act describes the need for participation in review and decision-making by incarcerated populations. In New York, this could be implemented through strengthened Incarcerated Liaison Committees (ILC) and expanded, empowered, and clarified independent oversight with consistent site visits and dedicated environmental monitoring.

Disaster and Evacuation Planning

From the failure to evacuate the Orleans Parish Prison before Hurricane Katrina to the 2023 immigration detention center fire in Mexico’s Ciudad Juárez that killed 40 men, the difficulties—and often deadly impossibilities—of evacuating a locked carceral facility have become clear. Despite the increased occurrence of wildfires and severe weather events intensified by climate change, prison evacuation procedures are often disordered or nonexistent, with shelter-in-place a de-facto policy.

While evacuation plans are protected by a Freedom of Information Law exemption, they should be made available to independent oversight organizations like the Correctional Association of New York (CANY), which could provide an assessment of that plan to the public. Given current and ongoing DOCCS staffing shortages, staffing as well as physical infrastructure should be evaluated.

Decarceration and Parole Reform

In New York, even as overall incarceration rates have fallen, the parole process still leaves the most vulnerable populations—defined by the Environmental Health in Prisons Act as those “at higher risk of exposure to environmental stressors or higher risk of negative health outcomes from exposure to environmental stressors,” including “people who are older than 50 years of age,” “people who have preexisting medical conditions or take medications that can make them more susceptible to heat or cold,” and “people who have been substantially and cumulatively exposed to environmental stressors on account of the duration of their sentence”—in prison.

New York currently has two important bills that should also be understood as environmental justice legislation. First, Elder Parole (S2423/A2035) would allow incarcerated people over the age of 55 and who have served 15 or more years to go before the parole board. Second, Fair and Timely Parole (S307/A162), aims to increase releases among people already eligible for parole. This legislation would remove the parole board’s ability to deny parole solely on the basis of the “seriousness of the [original] offense,” a practice that is subjective and vulnerable to bias. Both bills would decarcerate vulnerable EJ populations susceptible to environmental harm because of their age or length of time spent in prison.